The schoolboy, the dental patient and the widow: Infected blood scandal victims share their stories

A five-year inquiry into how 30,000 people were infected with HIV and hepatitis after being given contaminated blood products to treat illnesses – with more than 3,000 dying – has concluded.

It revealed that the health service and Government led a “chilling” cover-up of the worst treatment disaster in NHS history with Rishi Sunak calling Monday a “day of shame” for the British state as he pledged comprehensive compensation.

Each of the victims has a story behind their struggle and here are five of them.

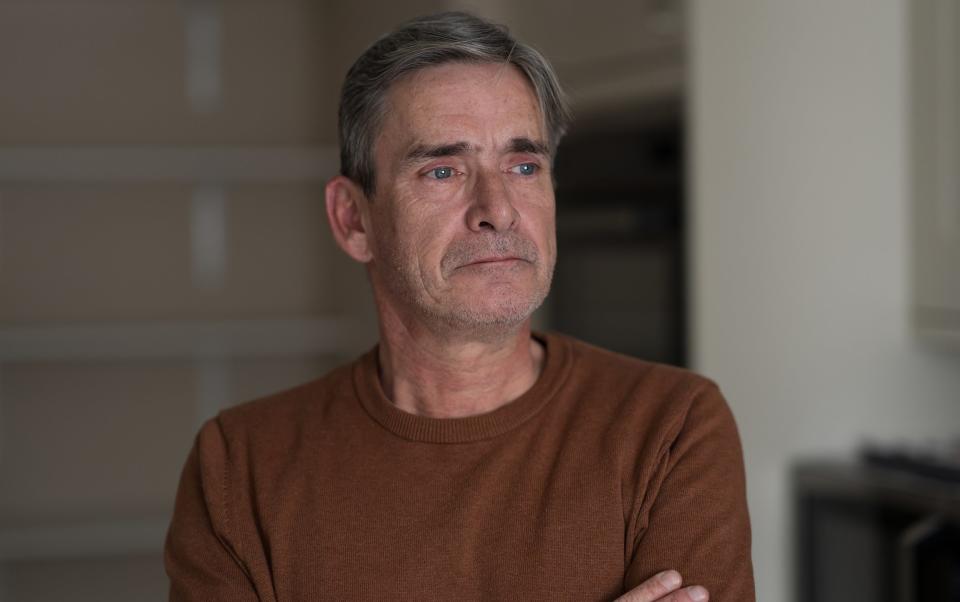

The Treloar schoolboy told he had just a few years to live: Gary Webster

When Gary Webster started boarding at Lord Mayor Treloar College in Hampshire, a school for children with physical disabilities, in 1975, life changed overnight.

After a childhood denied by haemophilia, he and his classmates were overjoyed with the newfound freedom a new miracle drug had given them.

Rather than spend hours waiting for cryoprecipitate, the previous treatment, to defrost, transfuse and take effect, whenever they had a bleed, day or night, they could simply get a dose of Factor VIII.

However, there were soon signs that something was wrong as Gary and his friends would end up bedridden with serious illnesses and become among the first patients in the UK to test positive for HIV.

Gary had realised not all was well and questioned why he was being given the drug every other day, but was told it would prevent bleeding. However, a friend had rightly speculated: “I’m sure they’re bloody experimenting on us.”

In their final few months at the school, in springtime 1983, Gary and the friend, then 17, were abruptly called out of class.

“I’ve got something to tell you,” a doctor told them. Both the boys had signs of a newly emerging illness, Aids. “It is incurable and we cannot guarantee you will be alive in two to three years,” he said.

They were among the first people in Britain to be diagnosed with the life-threatening condition, a year before HIV was discovered and the link between Factor VIII and the illness was accepted by the government.

“We just couldn’t believe what he was saying,” Gary, 59, told The Telegraph. “We were shocked but we were young. We looked at each other and half smiled. Then we went back to class.”

Only 30 of 122 pupils treated for haemophilia at Treloar’s are still alive and Gary has grown accustomed to seeing school friends grow poorly, witnessing their decline at regular reunions, and paying his respects at the funerals that followed.

“It got too hard,” he says. “Every time you went to the reunions there were less and less people. The funerals were every year from the late Eighties into the Nineties.

“I had a big group of friends who were haemophiliacs – and [then] there weren’t that many of them any more.”

Gary is only alive today thanks to breakthroughs in antiviral treatments which he was given in 1996 and brought him back from the brink.

“It was pot luck that treatment came in when it did,” he said “Others got ill too early.”

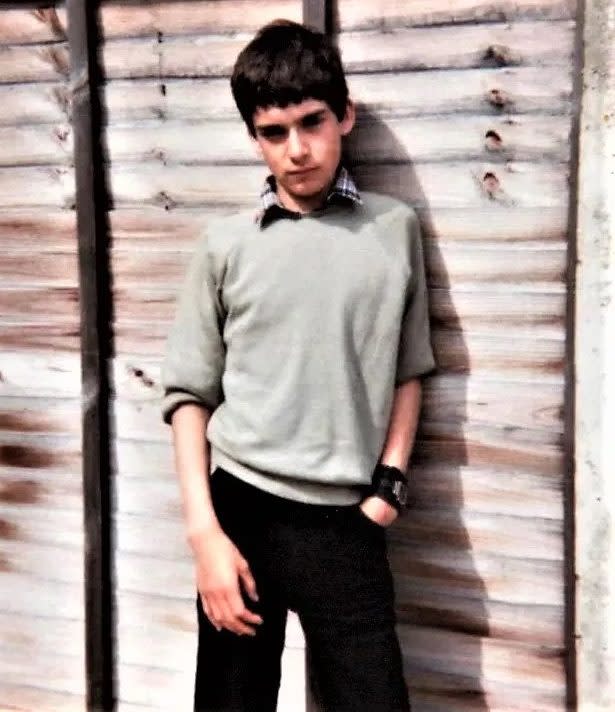

The dental patient who caught Hepatitis C: Mike Dorricott

Mike Dorricott was only 15 when a routine dental procedure in 1982 left him infected with hepatitis C which would eventually kill him.

A mild haemophiliac, he could have been treated with older medication and did not necessarily need the new “miracle” drug Factor VIII.

His dentist had suggested using cryoprecipitate for the procedure at Huddersfield Hospital to remove four teeth. But without his or his parents’ permission, the new disease-riddled drug was used instead.

Mr Dorricott, a marketing manager, only found out about the infection years later after the birth of his daughter Eleanor in 1996, when he went for a check-up at the Haemophilia Centre. He was referred to Addenbrookes Hospital for treatment of cirrhosis of the liver.

Until then his family thought his fatigue was from work, unaware of the real cause. He later had to receive a liver transplant in 2000 but five years later scans found cancer and he had to undergo another transplant.

However, cancer cells returned and Mr Dorricott died aged 47 in 2015 from liver cancer linked to the hepatitis C he had contracted through infected blood.

He had campaigned for justice over the scandal and a fair settlement for the victims and had met with Jeremy Hunt, while he was health secretary, who has promised to honour him with compensation.

His family told the inquiry that Mr Dorricot and Mr Hunt were “really good friends” and were on “first-name terms”. His wife, Ann, said a meeting had been held shortly after her husband’s terminal diagnosis to discuss a “fair and final settlement” for the victims.

“When Mike told the room that it was terminal, Mike got very upset, very emotional,” she said. “Towards the end of the meeting, Jeremy Hunt came to me and Mike, shook our hands and said to us, ‘don’t worry about this, we’ll sort it’. Those were his words.”

During evidence, Mr Dorricott’s daughter Sarah read a statement written before he died in which he told how “nasty, nasty, disease has completely shattered my life”.

He said: “The financial impact of this scandal is only one part of how this has affected me and my family. The chances are that I will be dead in the next 12 months. Nothing will ever repay this.

“I won’t be there for my wife and two daughters. I won’t get to walk them up the aisle. I won’t be there to see their grandchildren. My wife will be on her own.”

The woman forced to have an abortion at 7 months

Frankie* was pregnant when she received the devastating news that her husband had HIV.

Having never heard of the disease, Frankie was shocked when in 1985, her then-partner Joe*, 21, collapsed while working as an engineer in a hospital, leading to the diagnosis that would ultimately see doctors force her to have an abortion.

Joe had suffered from haemophilia and had been treated with Factor VIII.

“It looks like Aids kicking in,” a doctor told Joe when he went to hospital.

Frankie later found out he had unwittingly passed on the virus to her.

At the time, the disease came with a terrifying prognosis of two to three years at most and because the stigma was so intense, the couple kept it secret.

Cruelly, the diagnosis came at what should have been the happiest moment of their lives as Frankie was pregnant. She said doctors strongly advised her to have a termination and she recalls “misinformation and duress”.

“Aids meant that you were ‘dirty’, that you did things other people thought was inconceivable,” she told The Telegraph previously.

She was seven months pregnant, so had to be induced and Joe wasn’t allowed in the room and the medics were covered in protective clothes and equipment. “It was very lonely and unhappy,” she said.

At the end of the procedure, a doctor said “Women like me should be sterilised,” she says, fighting back tears. “That stays with you. I felt for many years that I was a murderer.”

The couple later separated and Frankie withdrew from family and friends. The stigma surrounding Aids was such that she couldn’t face admitting what had happened.

Frankie later tested positive for HIV herself.

It was only in 2015, 30 years later, that she told her mother and brothers what she had been through. “Before they thought I was wicked and horrible,” she says, because of how angry she had become as a result of the trauma. “Now they understand.”

Joe refused to take aggressive early medications like AZT, but survived until the introduction of effective antiretrovirals, as did Frankie.

“We were an expensive and expendable patient group,” he says. “That’s how many of us see it.”

*Names have been changed.

Widow who found out husband was dying on the eve of their wedding: Baroness Campbell

Graham Armstrong Ingleson was a burly Yorkshireman who was a haemophiliac. He liked to go for pints in the pub with his mates and drive around the countryside in his Mini.

Graham met Jane at college, where the young pair fell in love. Jane, now known as Baroness Campbell of Surbiton, later met Graham again after university at a house party in Croydon and rekindled their romance.

Graham, a haemophiliac, was taking his “miracle drug” Factor VIII, his “passport to a normal life”. He worked as a heating engineer and by 1987, the pair were engaged to be married.

In the summer of 1987, just two months before their wedding, the couple were told that Graham had HIV which would become Aids and he would likely die within five years.

“It felt like you slipped off the edge of the world,” Baroness Campbell told The Telegraph.

On their wedding day, Graham hoisted Jane out of their car for their joyous reception, but the cloud of the meeting with the doctor lingered over the couple.

“[The diagnosis] was less than two months before our wedding and my father died in a car crash around that time,” she said. “I think that was one of the worst times of my life.”

Graham’s condition deteriorated, and he could not work for the last two years of his life. The pair struggled for money, and because Baroness Campbell also had a disability, the pair needed more care than most.

“It was like being at war in your own house,” she said.”

During her emotional testimony to the inquiry, she recalled times when the two of them were too weak to be able to boil the kettle and make a drink, so they went thirsty.

Graham died on December 19, 1993. Baroness Campbell returns every year, on the anniversary, to St Botolph’s Church, where there is a book of remembrance for haemophiliacs who were killed by the scandal.

“Women were also giving up a lot. Many people forget what it did to marriages,” Baroness Campbell added.

“We just got married, but we didn’t have a marriage because we were too scared to enjoy the honeymoon years. A lot of us became nuns, not that we wanted to, but we thought it was the only way to keep safe.”

The son hounded over father’s HIV: Jason Evans

Jason Evans was just four when his father Jonathan died in 1993 having been infected with both HIV and hepatitis C.

Jonathan had been infected with both viruses while receiving treatment for haemophilia at a specialist centre in Oxford.

Tragically, Jonathan, who was born with haemophilia, had predicted Factor VIII could prove unsafe. Medical records showed he had raised concerns about the safety of the drug in 1984, the same year he contracted HIV.

Jason, who also had an uncle who was infected with both viruses and died in 1996, was born into the infected blood scandal in Coventry in 1989.

He still remembers his fourth birthday in 1993, when he visited his father at his grandparents’ house. His father was lying in bed, too weak to play with him. Six weeks later, Jonathan died of Aids-related illnesses.

In an example of the stigma attached to HIV at the time, there was a black “biohazard” symbol on his birth certificate marking him as the child of someone with HIV. He was tested for the virus on the day he was born.

When his father was diagnosed, his mother was sacked from her job at a cake shop. Her employer defended the decision saying “it could have been a real hazard” to keep her on as her husband could pass on HIV at any time.

The condition had taken a toll on the couple’s marriage as their relationship broke down and divorce proceedings began a year before his death.

Jason Evans had spent at least two birthdays at haemophilia centres and remembers playing with toys on their floors. For years he believed his father had died of a tragic accident but with time learned that his father could have been given safer treatment.

Growing up in a small village, he still remembers children at school who knew his father had died of Aids. By Year 4 or 5 he started to get taunted by other children who said “you must be the Aids boy”.

Whenever he asked his mother what had happened to his father, she would cry.

Evans became isolated, not only struggling to deal with the grief of losing his father but also the way he died. He played truant from school before finally going to college to study music production.

Now a father himself, Evans can recall his father’s funeral, at which he laid a rose on the coffin and said, “Bye bye, Daddy, I’ll miss you”.

“I have consciously thought about the agony I would feel at the idea of dying really slowly,” he said

“The idea of leaving your child is a nightmare. It’s the worst thing to think about.” He added: “It’s not one of those stories where he pulled through and we’re so grateful. He actually died and that’s the end of the story. It does suck to think about.”

Listen to Bed of Lies, a six-part Telegraph podcast laying bare one of the biggest medical disasters in history, the Infected Blood scandal, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your preferred podcast app.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport